An interview with “Saredo Media” on Somali politics, colonialism, and the future of women-led journalism

This interview was originally conducted and recorded via Zoom on May 18th, 2024 between Halima from Saredo Media and Stachka!’s two editors, Majorca Bateman-Coe and Jonah Henkle.

MAJORCA: First, I would like to allow you to introduce yourself more broadly before we get into more specific questions.

SAREDO MEDIA: My name is Halima, but my tagline is Saredo Media (@saredo.media) on Instagram. I am a former film student. I’m currently a trainee journalist, studying a multimedia journalism course. I’ve always been interested in film and photography. I tend to focus on East Africa and other parts of the world; I like researching Kurdistan and Eritrea, Ogaden Region, mainly those parts, because there are a lot of international struggles happening around the world, and I’m interested in showcasing their past or present.

MAJORCA: For our readers, where does the name “Saredo Media” come from? Does it have any linguistic significance? And what inspired you to choose this name for your project?

SAREDO MEDIA: Saredo is an authentic Somali name, but it’s written with an extra e, "Sareedo." It means someone blessed and prosperous. As it's an authentic and rare name, I decided to add it to my tagline because I felt like the name was so connected to historical meanings. It is so unique that I have never come across someone with the name "Sareedo.”

JONAH: Can you tell us more about those historical meanings, maybe some examples, and their significance to you?

SAREDO MEDIA: So, in terms of the name, I used it to evoke a potential revolutionary history. This name isn't talked about, and it's not like it's a very rare name. It's pretty. I picked it because I wanted to bring a backup name for my actual name for the whole thing.

MAJORCA: So would you say it's a unique name culturally specific to you?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah, it's a unique name in Somali culture. I've never come across someone whose name is ‘Saredo.’

MAJORCA: Interesting. So, my next question is, as someone working more independently as a journalist in training and covering topics that tend to be more out of the framework of Western journalistic interests, what is the biggest thing you hope to achieve from your work?

SAREDO MEDIA: I don’t like speaking about British news because it’s often colonial in its structure, often politically conservative, and it supports the monarchy. As someone who’s East African, I would love to focus and talk about Africa and other third-world countries as I can relate to their struggle in some way.

So, it gave me the idea to ditch that narrative and go to the more international and revolutionary side of news because we don't hear about revolutionary struggles outside of the Western sphere. So, pretty much, there are a lot of international organizations and international news outlets online that I have come across, like red., which has an Instagram page and broader leftist news outlet that tends to highlight a lot of ongoing international struggles, which I find very interesting. But also, I feel like people who are not showcased in the Western media are technically the ones who have a socialist view of the world, and they don't tend to get showcased as much.

MAJORCA: So, would you say your focus is sort of non-Western or like non-imperialist engagement and politics?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah, because I can resonate more with that than Western media. A lot of Western media tends to have an overwhelmingly negative and misleading narrative of countries I tend to report on, like East Africa and Kurdistan.

JONAH: Yeah, I mean, I think that, at least in Western media, especially the US around, you know, Arab Spring and these kinds of moments of political turmoil, there's always this intention to either cast, if they're supposed to be sympathetic characters, then they're like liberal and they, you know, want to turn the global South into something more similar the West, or if they're characters we're not supposed to support, then they, you know, there's all of these kinds of Islamophobic narratives that centers political assault and forms of military aggravation.

So, I think that it's, there's, you're doing important work in showcasing, you know, different ideological positions that are available, especially socialist positions that are often silenced or cast aside in Western media.

Left: Saredo Media’s graphic of Giorgio Marincola an anti-fascist partisan who was a member of the Italian resistance who fought against the fascist colonial regime.

A short biography about Giorgio Marincola and his life is available on Saredo Media’s Instagram page.

MAJORCA: My next question is related to actually our earlier discussion. I guess I wanted to ask about the sort of community that you've encountered. Have you found that people like in school or the community or people you've worked with are supportive or understanding of revolutionary journalism and these sorts of media-based explorations, which ties into your experience studying film?

Was it illuminating? Or did you feel that a lot or some of your ideas and perspectives were suppressed or ignored?

SAREDO MEDIA: I've organized with a couple of groups since I was studying at film college. I worked with different types of organizations. While organizing with two of them, I wasn't doing much news journalism work. I also used to do one for an organization that tends to like to have a British nationalist view, and I didn't like it. They weren't supportive of my perspective. But, at least at the moment, I currently like having a break from organizing, but the last organization I organized with, they actually have their journalistic revolutionary like a news outlet, which they sell like magazines, and it technically speaks about the Internationalist Youth in Europe and the Kurdish revolution[1], which is interesting.

[1] This is also known as the ‘Rojava conflict’ or the ‘Rojava Revolution,’ which is classified as a political upheaval and military conflict currently taking place in northern Syria, known to the Kurdish people as Western Kurdistan or Rojava, beginning in July 2012. After the autonomy of Rojava was declared by activists and other members of the Kurdish working class, the laws formerly passed regarding restricted political organizing, women’s freedom, religious and cultural expression, and other restrictive policies implemented by the Assad government were superseded and replaced by a Constitution of Rojava, also known as the Constitution of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, which granted minority rights, gender equality, and what would come to be known as ‘democratic confederalism,’ which blended private companies, autonomous administration, and other worker-led cooperative movements.

They inspired me to continue to bring Saredo Media to an ideally huge platform. At film college, only one teacher supported my stances; during one of our lessons, which was on production and development, he went. I made a poster about the revolution in Kurdistan, and he supported it. He even mentioned it and said that he supports the revolution there, and he feels like the media has a very negative outlook on it.

However, when I produced a couple of films related to anti-fascism and anti-Nazism at my film school, some of the teachers didn't like the output. One of the teachers was very uncomfortable with the whole project. So, I had to tweak some parts, which was hard to continue because it kind of destroyed the film's production and developmental flow.

JONAH: Just when you were talking about, you know, organizations you're organizing with, the organization that Majorca and I organized with has its newspaper called People's World. But, and it's great, don’t get me wrong– it publishes a lot of good stuff, but then there's a lot of limitations to working in that space, and especially, you know, when it comes to people who are kind of in the academic world, as well as in ‘activist’ spaces, whether that’s digitally or in person.

The two seem not even to recognize or acknowledge one another. The activist space doesn't recognize academic work, even if it's political, and certainly, the kind of stuff that our comrades would write in People's World doesn't always get recognized in academic spaces, either. So, I’d say we can sympathize.

MAJORCA: There's the constant push and pull, I feel, between those two kinds of worlds. This question is a little bit different from the previous one.

Now that you have been using social media to reach out, make connections, expand your community, and share information, how do you feel the platform's interconnectedness has benefited your work, and how do you think about writing and researching?

SAREDO MEDIA: Some of my followers are people I know. And a lot of them are apolitical. Many tend to have a negative view of politics and political discourse in general.

Connecting with my work with them has made them repost it, and many of them have been reposting and liking my content. I was genuinely shocked because a lot of them tend not to have an interest in politics, or they tend to have opposing views about what I post. There have even been a couple of like reposts that I've done on that account of articles circulated by red. about Turkey and its historical political involvement with Zionism.

And, and a lot of, I had to, I did a lot of reposting on my stories, mainly because a lot of the people that follow me, they don't know about the history, and they just believe that Turkey is an entirely good country, but, in reality, they're still committing a lot of ongoing war crimes in Kurdistan and Armenia, and even places like Syria and Iraq.

So far, my work has had a positive outlook. Many people have started engaging, and I'm hoping to make it even broader and potentially add it to X/Twitter and other spaces where young people are active, make magazines for young students around London, and even digital magazines for the youth around Europe, hopefully expanding my work around the world.

MAJORCA: I have a little quick follow-up that just came to mind. I think it's like, I mean, I especially know, like in Muslim communities, there's this sort of like romanticization of Turkey and Ottoman aesthetics. Everyone's like, “Oh, a vacation to Istanbul,” you know, there’s such a huge industry for tourism there. There’s also this rampant romanticization of the UAE and Dubai. Of course, these capitalistic nations have been more than complicit in ongoing war crimes in Sudan and other parts of the world.

Do you think that there is a process of demystifying within Muslim spaces, especially since you have sort of an interesting Muslim perspective or cultural background when it comes to this?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yes, definitely.

I want to center the current political narrative in historical contexts and educate people about what countries like the UAE and Turkey have done. My main goal is to educate Muslims because a lot of some of the followers that I follow are like people I know who I feel like Muslim and claim that they don't care about politics because they're like, “Oh, we don't want to be involved type of thing.”

When it comes to Turkey, I tend to speak about the fact that Kurdistan is also like a Muslim country that is getting oppressed by another Muslim country. People need to see the whole picture because many countries I mentioned exploit and manipulate the media they produce. Similarly, a lot of Muslims tend to look at primarily Western media sources. And they agree with some of the stuff without understanding its origins and context.

MAJORCA: Interesting. Thank you. My next question is more specifically about Saredo’s focus on Somalia and Somali political history and socialist political and ideological movements within the country. You've explored photojournalism and the Horn of Africa, the shortcomings of UN intervention in the Mad Mullah case, the 1976 Loyada hostage mission, and other interesting topics.

Above: A Somali woman holds a rifle for a man while he prays in a compound.

May 8, 1993, Photograph by Dan Eldon.

Why do you think it's important to focus on Somali politics, history, and other countries within the Horn of Africa, such as Ethiopia, Eritrea, etc.?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah. So, about Somalia– Focusing on and researching Somalia and Somalian history got me into journalism.

I have always been interested in researching my background, and I have gone to people around me who have taught me about Somali history. During the pandemic, I came across an East African photojournalist called Dan Eldon, who was killed in Somalia. However, in reality, he was a victim of, by extension, US imperialism. They hovered over his body and then turned away from him. They ultimately didn’t care for his safety as a journalist.[2]

[2] Eldon was involved in a major historical event in Somalia called ‘Bloody Monday.’ During the summer of 1992, Somalia experienced a major famine. Eldon was stationed in Mogadishu, capturing scenes near the US Marine landing there. In the following summer of 1993, Eldon, an Associated Press photographer named Hansi Krauss, Kenyan Reuters sound technician Anthony Manchuria, and Kenyan Reuters photographer Hois Maina were also murdered by top clan leaders of the Habr Gidr, a subclan of the Hawiye. The attack was ultimately interpreted as an act of vengeance– upon investigating the site of the US airstrike, the mob, seeing that the group of photojournalists and technicians were not locals, proceeded to target and stone the group.

He was a very interesting person in journalism. I spoke to Eldon’s parents and his mother, and they also told me about his life, how he was so eager to work in Somalia, and how it was a country of major journalistic interest to him.

Eldon’s main goal was to showcase the famine and the disasters of the UN, the UK, the US, and other imperial powers. These also included countries like Germany, Turkey, France, and Italy, all involved in the 1993 UN intervention.[3]

[3] The United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) is the second phase of the UN intervention in Somalia, which took place from March 1993 to March 1995. Before this, in December of 1992, former US President George H.W. Bush informed the nation that US troops would be sent to Somalia after the downfall of President Siad Barre in 1991 and the breaking out of civil war within the country. This mission would come to be known as ‘Operation Restore Hope’. It would eventually become the United Task Force (UNITAF), authorized under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. To maintain peace and assist with humanitarian aid, relief agencies, and the return of refugee populations, the mission aimed at economic rehabilitation and reconciliation through disarming Somali factions with military force. Although some civilian lives were protected and some humanitarian aid was ultimately distributed, UNOSOM II is largely considered a failure. Ultimately, the population continued to suffer, and the mission was plagued with severe and rampant mismanagement and internal corruption, resulting in 385 casualties of UNOSOM II forces from many different nations and an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 local Somali casualties. UNOSOM II ultimately withdrew in March of 1995.

Also, Somalia is very interesting in terms of the 1970s, when they won a war against Ethiopia, which was a revisionist tyrant at the time.[4] They were doing a lot of dirty work with revisionists, the Soviets, and Cuba, showing and showcasing their militaristic powers.

[4] This conflict is also known as the Ogaden War (1977-1978), which was fought over the sovereignty of Ogaden. The Ethiopian Army had received military supplies worth more than $1 billion from Cuban and Soviet forces, along with 12,000 Cuban soldiers and 1,500 Soviet military advisors led by General Vasily Petrov. What followed was the attempted ethnic cleansing of the Ogaden region of ethnic Somalis. Although the Soviet and Cuban advisors seemed to want to use Ethiopia to further the spread of socialist economic influence, the conditions were ultimately untenable and resulted in further political instability within Ethiopia and would later prompt the successive Somali wars for the remainder of the 20th century.

Somalia has also always been a country that has undergone many changes in its history, from fighting colonialism to fighting superpowers like the US and Ethiopia. It's interesting to understand how journalists managed to showcase their stories and the real issues that were going on during this time. To this day, Somalia is interesting because new journalistic platforms are being developed. Recently, there was one called Geeska, and it focused on Somali politics.[5] It also speaks about colonialism and photojournalism of all sorts.

[5] Geeska Afrika is a Somali-language Somalilandic newspaper owned by the Geeska Media Group, founded in 2006 and published in Hargesia, the capital of Somaliland.

Left: Per Geeska’s “About” statement section of their English-language website, they write:

“Geeska (The Horn) website is a cultural media platform that monitors political, cultural, economic, and security developments in the Horn of Africa region. It provides analyses, investigations, opinion pieces, and features in Somali, Arabic, and English languages. The website aims to establish a voice owned by the sons and daughters of the region, contributing to shaping the image of cultural media in the Horn of Africa.”

MAJORCA: My next question is a bit more about the media aspect of your work—and the film-based process of accumulating and organizing media. How has that process assembled information that may not have a super easily accessible visual form?

I suppose this question is more about a broader discussion of documentation or documentary film practice.

SAREDO MEDIA: Oh, regarding Dan Eldon’s work, more specifically, I haven't delved into it as “Saredo Media,” but I hope to in the future. His work tended to focus on the situation in Somalia during that time because he used to document and photograph many anti-American, anti-imperialist narratives.

He was also put at risk whenever he did this, which his mother told me about. She was like, he was going more broad in like, “oh, I have to report on this story.” A lot of his work has also been published in small books.[6]

Right: “The Journey is the Destination: The Journals of Dan Eldon,” derived from 200 pages of Eldon’s artistic journals and was compiled by Kathy Eldon with an afterword provided by Alicia Dougherty and a foreward by Kweku Mandela.

This film of the same title was released and distributed by Netflix in 2016.

[6] Eldon would also serve as the inspiration for a biographical film entitled, The Journey is the Destination, which would later be filmed in South Africa in 2014 and released on Netflix in October 2017.

I have and own three of them. I always look back at his work to get more inspiration for photojournalism and potentially make another side of Saredo Media, more of a digital camera side.

MAJORCA: Would you want to digitize and organize visual media in Saredo’s future endeavors?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah– I think I didn't mention another point I wanted to add. There are other journalists I learned from, like Dan Eldon, the journalist I met. He had a massive network of journalists he worked with. And many of them have different stories and inputs to put on Somalia, which is interesting.

MAJORCA: This next question is a little random, but I also saw that you have written some pieces on your Medium blog page in Somali. How has that process been? How do you hope to continue working on writing in Somali and distributing your work?

SAREDO MEDIA: Honestly, it's been quite hard because a lot of people, like some other journalists who do independent work for black socialists, focus on black socialism and many of their works.

They approached me and said, "Oh, could I please have this in English?” I was struggling to translate many of the things that I wrote. But I felt it was more powerful to say in Somali than English because Somali people have, like, oh, the piece that I'd done, Somalis tend to connect to that as the main history.

MAJORCA: This other question is also somewhat random, but it's more broad. This is a question that I feel like a lot of people who have ever been involved in journalism or have tried to compose journalistic works have struggled with. It's popular in mainstream media and has become a political question with pressing importance.

And that is the future of journalism. There's a tremendous amount of political suppression and censorship of leftist and anti-imperialist work in the West and in both the UK and the US. What are your hopes for the future of journalism? This can relate to working independently and making interpersonal connections among teachers and peers. So, what are your thoughts about this?

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah, I can relate to this, but I also have a strong view of what journalism is like now.

Many journalists are now banned from certain platforms such as TikTok and rely on Telegram to avoid issues with transparency and miscommunication and to have a layer of security in their work. At the moment, since I'm based in Europe, there's a likelihood that I'll be swarmed with Western imperialist news, which I don't want to be involved with.

I want to work more broadly in places like Somalia, where people always speak about history.

And I find it interesting. The future of journalism now is getting more young women involved in journalism because you don't tend to see a lot of young female journalists or socialists, female journalists who have their self-run outlets. And now it's growing.

I hope my platform and audience grow even more and get more people involved, potentially that commission for spaces in different socialist news outlets, big ones like red., or other journalists I can collaborate with who are socialists.

JONAH: You brought up something really interesting: the emphasis on understanding and re-understanding international communities. Since there's a tremendous amount of Western misinformation and a lack of cultural understanding or cultural isolation, Western powers depend wholly on intellectually isolating the people within their communities to uphold their imperialistic power structures.

MAJORCA: That's good food for thought. Finally, I wanted to return to finding relevant media or assembling source materials when presenting work online.

If you could choose one image or a piece of media, film, documentary, or newsreel that has stood out to you the most while researching and organizing your work, this can be like a historical moment, a portrait, or an image of a landscape. What would it be and why?

SAREDO MEDIA: It would be a picture of a journalist.

I think he was in Nepal and had a huge camera recorder. There was a Nepalese man, and she was curious about the camera. I have other pictures. Is there a specific one you want me to pick or…?

MAJORCA: I guess if there's one that you feel like has sort of maybe changed your perspective or something that you feel like you could talk about or maybe that, like you kind of mentioned this example, like a picture that has more of a story and perhaps requires a certain political context or prior education to understand it better.

SAREDO MEDIA: So, a picture of a Somali guy in a protest, which is an anti-American protest. And I think Black Hawk helicopters are flying, which are like the US imperialist helicopters.

Above: Conflict and unrest in Somalia. Photograph by Dan Eldon.

“After my first trip to Somalia, the terror of being surrounded by violence and the horrors of the famine threw me into a dark depression. Even journalists who had covered many conflicts were moved to tears. But for me, this was my first experience with war. Before Somalia, I had only seen two dead bodies in my life. I have now seen hundreds, tossed into ditches like sacks. The worst things I could not photograph… I don’t know how these experiences have changed me, but I feel different.” – Dan Eldon

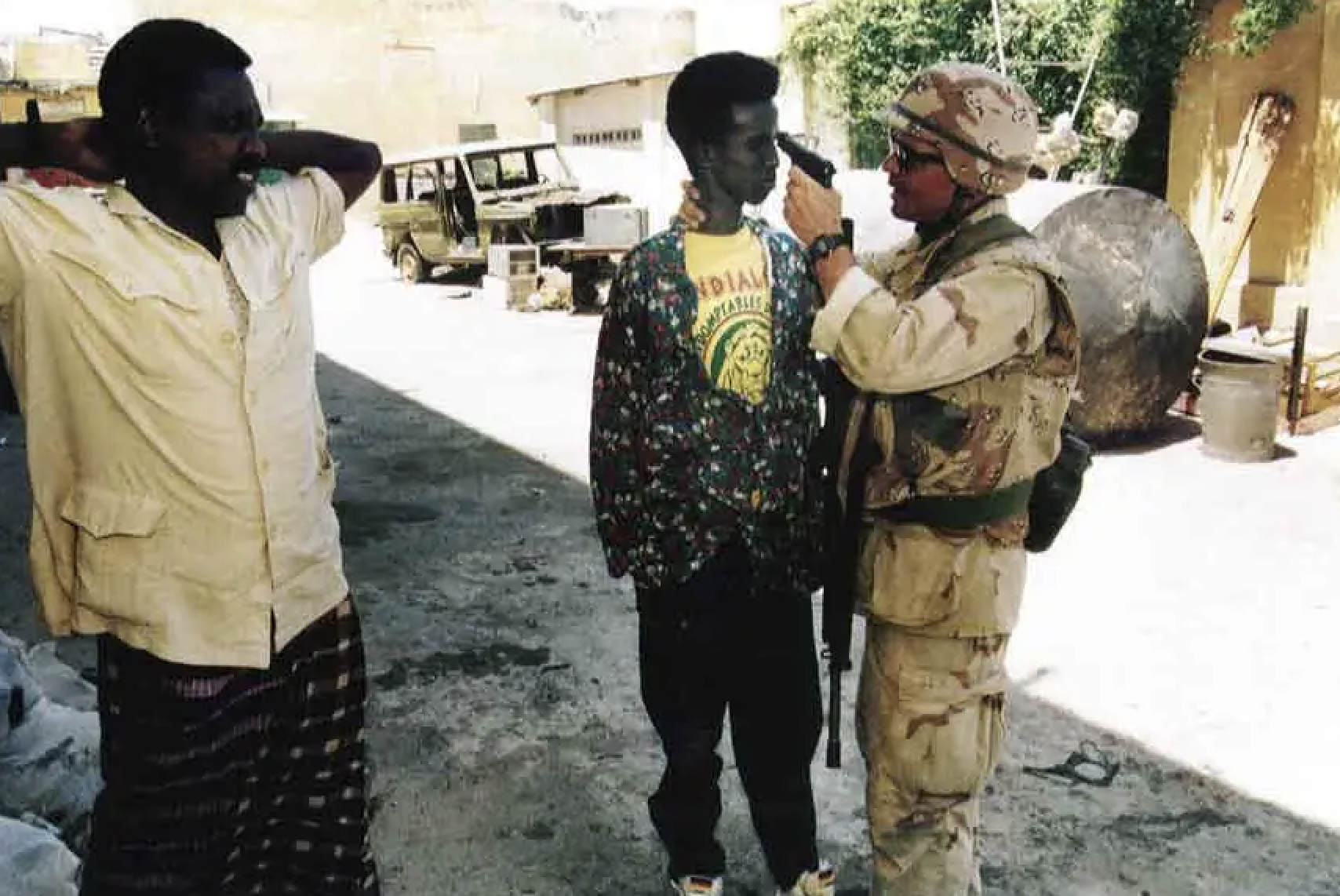

In the image, from what I remember, the man raises the Somali flag. And there's another one where a man's walking and a US Marine soldier in Somalia, and he just gives him a very angry, powerful look, which has so much context with colonialism and anti-imperialism and the full process of how colonialism was so powerful in Somalia and how people have a strong hatred for it deep in their hearts.

Above: A Western soldier tauntingly holds a pistol up to the forehead of a Somali man, who regards him sternly. Photograph by Dan Eldon.

JONAH: Is there anything else that you wanted to add or say that we could incorporate into the conversation that you feel, you know, that you want to have be heard that didn't come up in conversation?

SAREDO MEDIA: International students interested in socialism, anti-colonialism, or anti-imperialism are welcome to engage with my content! Feel free to message the account on Instagram DMs or send an email to saredo.media@outlook.com for further inquiries or requests for collaboration.

MAJORCA: Thank you so much for your time.

SAREDO MEDIA: Yeah. Thank you. Yeah, thank you so much.

Interested in keeping up with Saredo Media’s work? Click on the links below:

Medium